What can a paper from 1987 teach us about delivering software today?

The paper in question is No Silver Bullet - Essence and Accident in Software Engineering, by the late Fred Brooks (pictured). Brooks was a computer scientist and software engineer, best known for his influential book The Mythical Man Month.

It is a fascinating paper! Not only because it predicts many of the ensuing developments in our industry, but also for its wonderfully flowery prose:

Of all the monsters who fill the nightmares of our folklore, none terrify more than werewolves, because they transform unexpectedly from the familiar into horrors.

They don’t write ‘em like that any more. But what have werewolves and silver bullets to do with software? Well, the werewolf in this tale is Complexity, and the eponymous silver bullet is something that would ‘lay it to rest’.

Developers, by-and-large, do not set out to build complicated systems. Yet, like the universe tending towards entropy, they have a knack of ending up that way. Can we learn anything from Brooks’ paper to help avoid this?

Complexity

Software systems are complex entities. Perhaps, according to Brooks, the most complicated human constructs ever conceived. It is this complexity which is the root of a lot of problems associated with the development and delivery of software.

Complexity is rife in all aspects of systems development, and perfidious. It leads to missed deadlines, unmaintainable systems, and employee churn. It seems this was understood even back in 1987 - Brooks’ paper is effectively a cogitation on different ways to attack that complexity.

Brooks identifies two types of complexity: Essential and Accidental.

Accidental vs Essential Complexity

The idea of accident vs essence was something first articulated by Aristotle (no less!). The essential properties of an object are those which are necessary, that make the object what it fundamentally is. The accidental properties are contingent, they are properties that the object also happens to have, but are not related to its essence.

An example quoted here is that of a chair: a chair can be made of wood or metal, but this is accidental to it being a chair. The essential property of a chair is of it being something we can sit on.

But how does this relate to software? Well, quite neatly in fact.

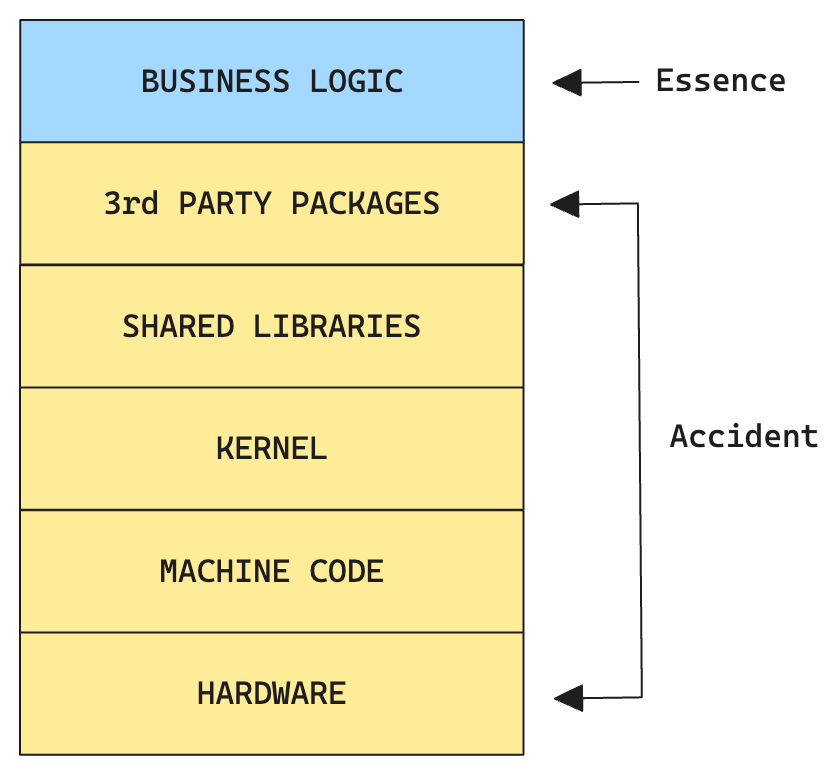

If we consider a piece of software in all of its constituent parts, we can envisage it as a layer cake:

The Essential Complexity, in modern parlance, could be considered as the Business Logic. The part of the software that carries out the particular set of actions that…does the business. The part which differentiates this piece of software from all others.

This implies that all of the layers beneath the Business Logic are the accidents. They are not fundamental to the nature of this piece of software. This does stand to reason: consider the same piece of Business Logic running on a Linux vs a Windows machine. It would still be doing the same thing, but most of those lower layers would be entirely different.

But what can we do with this knowledge? How do we attack (Brooks’ term) these different types of complexity?

Attacks on Essential Complexity

Naturally the essential complexity of a system is the hardest one to tame. In fact the whole thrust of Brooks’ paper is that this is the werewolf which will not be slain.

Interestingly, the modes of attack which Brookes described in 1987 are very much still relevant today:

- Good Software Design: obviously. In fact, since Brooks’ time many software design principles have been floated: DRY, OOP, YAGNI, the SOLID principles, functional programming etc. We’ve mostly come to agree that a degree of pragmatism is required in choosing which ones to follow. It is fair to say that this is still not a solved problem, nor is it ever likely to be.

- Training Engineers: again, this should be obvious. Training, mentoring, guiding the career, and in general being respectful of, the next generation of software engineers is crucial. (How else are they going to unravel all that awful code we wrote!?). Our industry has become a lot better at this over the last 10 years or so, but there is always room for improvement.

- Rapid prototyping and growing software incrementally. This idea must’ve sounded novel in 1987. In the intervening decades - thanks to the march of Agile and treating software with a product-mindset - it has become common sense.

As engineering leaders, the above bullet points encapsulate what we should be doing to attack Essential Complexity. They are wide-ranging bullet points, for sure. But they boil down to: developing and designing software in such a way that it is easy to understand, and teaching others to do the same.

Attacks on Accidental Complexity

There is better news when it comes to attacks on Accidental Complexity.

In the layer-cake example given above, all of the layers designated as Accidental are in fact no less complicated than our essence, our Business Logic. Indeed in many cases they are wildly more complicated (compiling to machine code, for instance). Each of the layers has its own essence (and probably its own accidents), but they present as accidental to us.

This is entirely in keeping with the direction of travel seen by our industry over the past couple of decades: the abstracting away and commoditisation of essential complexities. What’s more, this has led to enormous gains in productivity.

Take compute hardware for instance; clearly an accidental property for most systems. Yet before the second decade of this century it was still an essence for many businesses with a serious tech presence. Then cloud computing came along and consigned it to being a mere accident. To the vendors of cloud compute of course, hardware is very much an Essential Complexity.

Brooks saw this coming, coining a term that we still use today: Buy vs Build

Buy vs Build

The most radical possible solution for constructing software is to not construct it at all

This is an idea that has been re-phrased and re-packaged over the years - Adrian Cockroft’s ‘avoid undifferentiated heavy-lifting’, or the shifting right on a Wardley map - yet still remains an absolute truism: when building software we should take advantage of whatever prior art exists, and concentrate most on the part that sets our software apart.

In practice this means using third party offerings wherever possible. Third party offerings could be a Cloud Provider, a SaaS product, open source libraries, or software developed by other orgs within the same business. In accepting these offerings we greatly speed up development (consider the time saved by not building these things), and take advantage of all the prior (and ongoing) care and attention that the maintainers of them so diligently apply.

I would apply this philosophy with extreme rigour, especially in smaller organisations with a need to quickly get to market. The single issue that Brooks cites with this approach is applicability. Does that off-the-shelf package fit my needs? The answer is very rarely Yes, Totally! There will be trade-offs, but the thing being traded is a great deal of development work up-front, and a great deal of complexity going forward.

Summary

The werewolf of Essential Complexity is not about to be slain any time soon. We can do our best to tame it by applying all the things we already know: build software incrementally, in a way that is easy to maintain, and train others to do the same.

Accidental Complexity, on the other hand, can and should be avoided at all costs. By availing ourselves of the shoulders of others, we can become even greater.

I would add one more observation: we should continuously look for opportunities to relegate Essential Complexity to the ranks of the Accidental. This is a harder one to sell, as it often requires some development work to extricate ourselves from our previous essence. But that work pays down a lot of future maintenance and will ultimately lead to leaner organisations.

Thanks for reading!